|

|

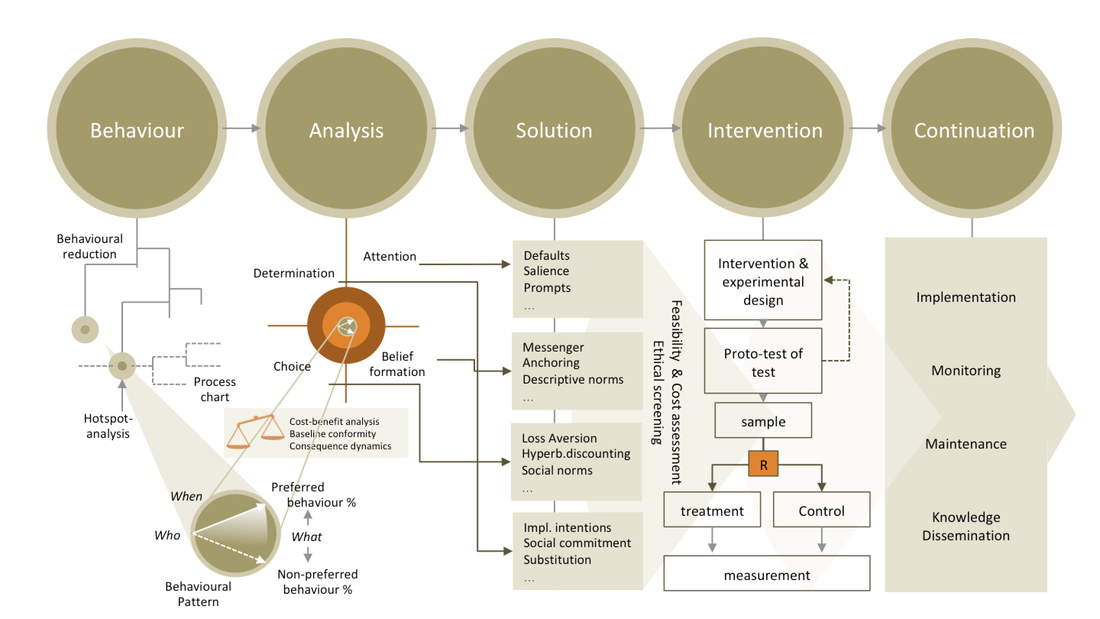

The application of Behavioural Insights in Public Policy, i.e. Behavioural Public Policy, has definitely come to stay. Reports such as MINDSPACE, EAST and Test, Learn and Adapt as well as the brilliant case collection Behavioural Insights and Public Policy published by the OECD has spurred the interest and motivation of public policy makers and behavioural scientists alike. Little, beyond inspiration, has, however, been written about how to actually apply Behavioural Insights in Public Policy; that is, about the processes, tools and challenges through which a BI-project usually progresses. In particular, almost nothing has been written about how BI-specialists approach a policy issue in behavioural terms as well as identifies suitable Behavioural Insights to apply in order to ensure an effective and responsible policy intervention. To close this gap, Karsten Schmidt and I recently published a new framework for applying behavioural insights in the Journal ‘Politik & Økonomi’. The framework is called BASIC: A Diagnostic Approach to the Development of Behavioural Public Policy and is a result of the almost 10 years of work with Behavioural Insights we have carried out at iNudgeyou – The Applied Behavioural Science Group. What is BASIC? Like EAST and MINDSPACE, BASIC is an acronym. It stands for ‘Behaviour’, ‘Analysis’, ‘Solution’, ‘Intervention’ and ‘Continuation’. BASIC is intended to provide prospective BI-specialists with a detailed framework for developing Behavioural Public Policy from the beginning to the end of a BI-project. It does this by presenting tools for:

BASIC is not only distinguished from earlier frameworks like MINDSPACE and EAST by encompassing the whole process involved in BI-projects. It also distinguishes itself by being diagnostic – a feature captured in BASIC by means of a theoretical framework which systematically relates the ANALYSIS of BEHAVIOR to that of identifying what Behavioural Insights to apply as potential SOLUTIONS. The paper mentioned above is a conceptual paper and therefore mainly accessible to those already quite familiar with applying Behavioural Insights in Public Policy. (In addition it is published in the journal Politik & Økonomi and is thus in Danish). Fortunately, in 2018 a much more comprehensive and detailed version of BASIC, including tools and ethical guidelines, will be made accessible for prospective BI-specialists as part of a toolkit for policy makers that will be developed with and published by the OECD.” UK Abstract Hansen, PG & Schmidt, K 2017, 'BASIC: En diagnostisk tilgang til udviklingen af adfærdsbaseret offentlig politik' Oekonomi og Politik, vol 90, no. 4, p. 40-53. For the past 10 years, we have witnessed the emergence of a new evidence-based policy paradigm, Behavioural Public Policy (BPP), which seeks to integrate theoretical and methodological insights from the behavioural sciences to public policy development. However, the work with BPP has been characterized by being unsystematic as well as centred on best cases, which neither specify the prerequisites for, nor the processes involved in, the development of BPP. This article presents BASIC; a diagnostic approach to integrating theoretical and methodological insights from the behavioural sciences in the development of behavioural public policies, as well as ABCD, which is a model for systematic behavioural analysis, development, test and implementation of behavioural insights. The overall model enables researchers as well as public employees to better understand the phases involved in the development of sound behavioural policies and how relevant behavioural insights are identified as the basis for effective policies.

Yesterday a friend of mine – Rafael Batista – got engaged in a Twitter discussion (he often does) about an article at The Conversation titled How ‘nudge theory’ can help shops avoid a backlash over plastic bag bans.

We had already discussed why the article conceptually gets nudge-theory quite wrong, but that’s for another day. This is all about the power of footprints

Some years ago my students and I conducted an experiment using stickers of green footprints leading to dustbins to get people not to litter. The experiment as well as the very idea of using footprints to prompt pro-social actions turned out to be quite successful (it has now been replicated in other countries) and popular.

Perhaps a bit too popular at times. Thus, in the article the authors write: “Such a strategy [behavioural nudges based on minor adjustments to the environment] could be applied in supermarkets where “footprints” could lead to reusable bags that are available for purchase. Repeating this over time could result in consumers associating the footprints with a reminder to bring their own bags. Varying the location of the footprints, or even their colour or shape, might encourage shoppers’ curiosity and thus increase the likelihood of consciousness about the plastic bag ban.” Now Rafael was not impressed by this passage and asked for my opinion. So, here it is. … “footprints” could lead to reusable bags that are available for purchase

My first thought here is: How?

Now footprints are not magical wands that we automatically follow to their destination where after we unconsciously perform some action that they don’t even convey. So why should footprints work in this situation? Is the hypothesis that they should work as an in-store reminder to by re-usable bags instead of bags at the checkout (assuming that this is where they get the bag in the status quo)? If so, this might work for some people, i.e. people who would be willing to pay for re-usable bags instead of getting them for free. Footprints would remind them about the existence of reusable bags before they queue by making that option salient. That is, if they accompanied with semantics telling that they are about buying re-usable bags. How should people otherwise know what they were about and be reminded of what they need to remember? Yet, we should not forget that nudges – especially attention-based nudges such as salient aspects of choice architecture – work in interaction with the underlying choice architecture (which for me is the rational choice structure, not to mistaken with Thaler & Sunstein’s notion of choice architecture which is broader). And the choice architecture, if I read the article correct, has incentives pointing in the direction counter to the nudge: free bags at the counter vs. re-usable bags that costs money. This is not good. However, it seems to me that salience can be used to trigger the Spotlight Effect when applied in public space, whereby existing social norms or status norms may be supported. That was the effect my students’ experiment with the footprints aimed at doing. Yet, this would require that the action (buying re-usable bags rather than choosing the free ones) should be as publicly visible as possible. For instance, reusable bags could be placed mid-aisle before the checkout queue or prompted by staff at the point of purchase. (I also have some much better ideas about how to decrease the use of plastic bags, but those will have to wait until someone steps up and commits to testing them.) But so far so good: footprints could work as part of an intervention, but not as simple as probably not as central as the article portrays. Next. Repeating this over time could result in consumers associating the footprints with a reminder to bring their own bags

This assertion is weird to me. An association of the footprints with bringing a bag doesn’t work when the reminder occurs in the store. Or, at least, that would require that people should be willing to go back home to get a bag when they see the footprints in-store.

I don’t think that they will be willing to do this. I wouldn’t. However, this assertion strikes me as very similar to the kind of assertions currently promoted heavily by fake “behavioural experts” when talking about behavioural economics and habits (“90% of our behaviour is sub-conscious!”, “A fly in the urinal primes you to eat beef!”, We need to change human habits to get people to save for pensions!”) But as the authors of the article really don’t seem to belong to that category AT ALL, I’m inclined to think that I might be missing something in the idea they put forward – because it just seems a weird suggestion to me. So I think they would have to elaborate on their suggestion in order for us to assess this properly. Next. Varying the location of the footprints, or even their colour or shape, might encourage shoppers’ curiosity and thus increase the likelihood of consciousness about the plastic bag ban.

,This is also just weird to me – unless you read it as a piece of beautifully formulated satire.

First, what is the purpose of “increasing the likelihood of consciousness about the plastic bag ban”? While its sounds clever, why would you? That is, why would we want to put up footprints to ‘increase the likelihood of consciousness” about this in-store? If there’s a ban, people will find out with a likelihood of 1 anyway as soon as they get to the counter… and why are we talking about a ban now? Weren’t the point something about nudges? Still, reading the sentence saved my mood for at least a couple of days. So what about the first part of the sentence? “Varying the location of the footprints, or even their colour or shape” to encourage shoppers’ curiosity. I think that suggestion is just a bit weird as well. Why would you want people to be curios and what should they be curious about? The plastic bag ban? Why??!! Or, is it still attached to the nudge, i.e. the idea of footprints working as a reminder that you should get some re-usable bags rather than take the free ones at the counter? If so, why would you ever use curiosity as a mechanism here? I don’t get it. What is it supposed to do that mere salience provided by footprints won’t take care of? Perhaps it is because the authors’ think like many others, that salience needs semantic novelty to sustain itself as a reminder. It doesn’t. Rather it usually needs semantic stability to become sustainable. If we varied the sound or even the sensory channel of bells on bicycles (yes, I’m from Denmark, so we have to use that as an example), then I would be dead long ago. A ring today, birds whistle tomorrow, stroboscopic light the day after – my brain would be confused and unable to make any stable association for the salient stimuli to serve as a reminder. I remember when some people suggested this about the footprints and litter bins in Copenhagen. Green today, then blue next month, then yellow… Now that would just ruin top-down salience. People wouldn’t know what to look for when in need of bin. So, Rafael, I completely agree with you.

I’m not impressed by the passage either.

Of course, I do believe that nudge-theory can help supermarkets reduce plastic bag usage…. And in ways much more elegant and effective than the 5-cents tax that a lot of people have fallen in love with or a ban that may backfire in a new market for re-usable plastic bags. Still, presenting those have to wait until we have tested them.

On June 8, 2017, I was part of a Roundtable at the Conference #NudgeInFrance held in Paris by Nudge France on 'The Limits of Nudge: Ethics & Manipulation'. Together with Cass Sunstein, Anne-Lise Sibony and Mariam Chammat we had a lively discussion led by Elsa Savourey from NudgeFrance. Prior to the panel we were send some questions for reflections, my notes on which I thought was worth sharing for those who couldn't attend, or was too busy listening to make their own notes. The notes will be shared over the next couple of days.

Elsa: As an introductory question: is nudge always “for good”? Are there nudges "for bad"? Are such considerations in relation to good or bad nudges integrated in the definition of what is a nudge? Pelle: A nudge is defined as a psychological function of any attempt at influencing people’s judgment, choice or behaviour in a predictable way, that is (1) made possible because of cognitive limitations, biases, routines, and habits in individual and social decision-making posing barriers for people to perform rationally in their own self-declared interests, and which (2) works by making use of those limitations, biases, routines, and habits as integral parts of such attempts, see (Hansen 2016). In particular, this implies that a nudge is intended to cause a behavioural effect independently of (i) forbidding or adding any rationally relevant choice options; (ii) changing incentives, whether regarded in terms of time, trouble, social sanctions, economic and so forth, or (iii) providing hitherto unkown factual information and rational argumentation. From this it is seen that the definition does not imply any normative criteria for an aspect of an intervention to qualify as a nudge. It includes interventions that may usually be evaluated as “nudges for good”, e.g. decreasing the unit size of cakes served at a buffet to reduce intake of sugar and fat; as well as interventions that may usually be evaluated as “for bad”, e.g. increasing the unit size of cakes served at a buffet to increase intake of sugar and fat. Both interventions utilize behaviour changing functions that qualify as nudges. Elsa: Nudge plays to mostly unconscious factors. Aren't people who are nudged just manipulated into a given choice? Pelle: First, I have to say that I’m not sure that I agree with the premise of this question. I think it is a widespread misunderstanding that Nudges mostly play on unconscious factors. It’s not a coincidence that many people tend to think this. First of all, many academics talk straightforward about cognitive bias and heuristics as unconsciously influencing our behaviour. Second, some of the most memorable behavioural insights from behavioural economics and cognitive- and social psychology are those that really surprise and fascinate us – and those insights that really surprise and fascinate us are typically those that influences our behaviour in a way we may label “unconscious”. Hence, due to availability bias, they are the examples that come to our mind when we happen to think about what characterizes nudges. However, from a scientific point of view we should be more careful when we describe how nudges work. As Cass described it in his keynote, dual process theories often explain their findings in terms of system 1 and system 2 cognitive processes. System 2 processes are what we call ‘reflective’, and as such they are consciously accessible to our inner experience by definition. This leads many people to believe that System 1 processes must be unconscious. But if you listened carefully to Cass he did not characterise system 1 processes as unconscious as such, but – quite correctly – characterized system 1 processes as automatic and intuitive, where automatic means non-intentional. And here is the important point: that cognitive processes are automatic and intuitive doesn’t imply that they are unconscious in the sense that they are invisible to our ‘inner eye’. The substitution heuristic provides an example of this. We often answer a complex question by answering a similar, but simpler one. On an everyday basis this usually works quite fine for our purposes, but it always comes at the cost of precision and correctness. Now, while the substitution heuristic is automatic, we can actually recognise it from our experience; and knowing of the heuristic and attending to our thinking we may even experience it as it happens and decide to reject the result of our own thinking. It’s not that it’s possible for us to do this all the time. It requires way too much effort and attention. But it is possible, which shows us, that we can actually experience, monitor and sometimes even override some of our automatic processes. They are not necessarily ‘unconscious’, but they are often non-conscious. So that was the premise. What about the question? "Aren't people who are nudged just manipulated into a given choice?" Now, we just drew a distinction between automatic and reflective processes based on Kahneman’s Dual Systems Theory. Following our earlier paper “Nudge and The Manipulation of Choice” (Hansen & Jespersen 2013) this distinction may also be used to distinguish between ‘choices’ and ‘behaviour’, such that choices are by necessity behaviours resulting from reflective processes, while behaviours caused mainly by automatic processes cannot be described as such (even though this is usually done in the micro-economic lingo that underpins most discussions of nudges and behavioural insights). Of course, this is a conceptual distinction and thus it runs the danger of simplifying too much. Yet, I believe that it does improve what we can articulate about the ethics of nudge, since this distinction makes it clear that not all nudges are aimed at influencing choices as such. From an ethical perspective this is an important point. Core concepts of ethics such as ‘responsibility’ presuppose agency and are thus tied to the category of choices. From an ethical point of view then, nudges aimed at influencing choices should be carefully considered as they result in those nudged obtaining responsibilities. In particular, if nudges are about manipulation, then we have a problem since this would mean that we could be manipulating people into making choices for which they, and not us, have the responsibility. Yet, it should be noticed from the outset, that nudges aimed at influencing choices, although most relevant from an ethical point of view, are only a sub-category of nudges aimed at influencing behaviours more generally and as such any conclusions pertaining to the former does not necessarily generalise to the latter. Still, the main question hinges on whether nudges are manipulative as such. In order to answer that question we need to draw an additional distinction. This is the distinction between what we have called epistemic transparent and non-transparent nudges; a distinction aimed at distinguishing between the manipulative uses of nudges from other types of uses, see (Hansen & Jespersen 2013). Also, it is coined to capture the general intuition referred to by Thaler and Sunstein’s when they say that an attempt at influencing other people’s behaviour, including choices, may be objectionable, “because it is invisible and thus impossible to monitor” (Thaler & Sunstein 2008, 246). Revising our 2013 paper a bit, I now define a transparent nudge as any nudge part of an intervention provided in such a way so that those affected can infer three things about the intervention as a result of the intervention:

A non-transparent nudge, on the other hand, will be defined as a nudge working in a way that those nudged cannot reconstruct the architect, intention, or the means by which behavioural change is pursued. A couple of points for those of you who want to dig further into this definition: The notion of transparency defined here is very close to what Luc Bovens refers to as “token interference transparency” in (Bovens 2008) although the present notion is more specific. Also, for those of you interested in ethics and philosophy, you may notice, that since subjects should be able to infer these three things as a result of the intervention, a transparent nudge is defined in such a way that it qualifies as a basic speech act providing what (Austin 1962) called ‘uptake’. Finally, for those of you more interested in ethics and the applied aspects of behavioural science, you should notice that epistemic transparency may vary according to the epistemic competencies of those nudged, i.e. epistemic transparency is defined as an empirical, and not a normative concept. Returning to the argument: defined as such, a transparent nudge is by necessity not a case of manipulation, when we understand by “manipulation” the psychological sense of the concept that is relevant for a discussion of ethics; that is, manipulation in the sense of intending to change the perception, choices or behaviour of others through underhanded deceptive, or even abusive tactics. Thus, to the extent that a nudge is transparent people are not being manipulated into a behaviour, let alone a choice. Elsa: How then do we determine whether a nudge is ethical or not? The answer to this question will be posted in the near future. Sign up for news, if you don't want to miss it. References: Austin, J.L. (1962) How to Do Things With Words. Cambridge (Mass.) 1962, paperback: Harvard University Press, 2nd edition, 2005. Luc Bovens (2008) 'The Ethics of Nudge', in Till Grüne-Yanoff and Sven O. Hansson (eds) Preference Change: Approaches from Philosophy, Economics and Psychology (Berlin and New York: Springer, Theo- ry and Decision Library A, 2008). Richard Thaler & Cass Sunstein (2008) Nudge – Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press 2008) This piece was originally published on Behavioral Science & Policy Association's Policyshop Blog in August 2016. Over the past four decades, advances in the behavioral sciences have revealed how human behavior and decision-making is boundedly rational [1], systematically biased, and strongly habitual owing to the interplay of psychological forces with what ought to be, from the perspective of rationality, irrelevant features of complex decision-making contexts. These behavioral insights teach us how contextual aspects of decision-making may systematically lead people to fail to act on well-informed preferences and thus fail to achieve their preferred ends. In the domain of public policy such advances may also teach us how neglecting these insights can be responsible for the failures of policies to reach intended effects and why paying more attention to them may provide the key for dealing more effectively with some of the main challenges modern societies and organizations face. Nudge In their popular book Nudge – Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (2008), Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein suggested that if a particular unfortunate behavioral or decision making pattern is the result of cognitive boundaries, biases, or habits, this pattern may be “nudged” toward a better option by integrating insights about the very same kind of boundaries, biases, and habits into the choice architecture surrounding the behavior – i.e. the physical, social, and psychological aspects of the contexts that influence and in which our choices take place – in ways that promote a more preferred behavior rather than obstruct it. In particular, they argue that such nudges may avoid some of the challenges and potential pitfalls of traditional regulation, such as costly procedures and ineffective campaigning, unintended effects of incentivizing behaviors, and invasive choice regulation, such as bans. The advantage, they claim, of applying nudges is that public policy makers might thus supplement – or, perhaps, even replace (Thaler & Sunstein 2008, p. 14) – traditional regulation with nudges to influence people’s everyday choices and behaviors in cheaper, less invasive, and more effective ways. That is, nudging seems to offer policy makers an effective way to influence citizens’ behavior without further restricting freedom of choice, imposing mandatory obligations, or introducing new taxations, or tax reliefs. Thaler and Sunstein coined the seemingly oxymoronic term, libertarian paternalism, to characterize the attractive regulation paradigm that intuitively arises out of the nudge strategy to behavioral change in public policy making, when it is enacted to serve the interests of the citizens as these are judged by themselves, see (Hansen 2016). In their original definition – or rather characterization – of what a nudge is, the absence of traditional policy strategies is even invoked as a formal condition: “A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.” (Thaler & Sunstein 2008, p. 6) However, as I have later pointed out in The Definition of Nudge and Libertarian Paternalism – Does the Hand fit the Glove? (2016) this way of defining a nudge easily conflates what is a descriptive behavioral concept with that of the separate political doctrine of libertarian paternalism. Instead we should define a nudge in a precise and consistent way relative to the behavioral sciences. In particular I suggest that we should adopt the following definition: "A nudge is a function of (condition I) any attempt at influencing people’s judgment, choice or behavior in a predictable way (condition a) that is motivated because of cognitive boundaries, biases, routines, and habits in individual and social decision-making posing barriers for people to perform rationally in their own self-declared interests, and which (condition b) works by making use of those boundaries, biases, routines, and habits as integral parts of such attempts." (See Hansen 2016 for a discussion of this definition) By this definition, the operational independence of nudges as to regulation is not a formal condition, but an implication. That is, the original definition of a nudge provided by Thaler and Sunstein (2008) is actually a consequence of the more fundamental definition provided here. This is an important point because it means that even though nudges can operate independently from regulation, they are not required to do so. Thus, a nudge may be combined with traditional regulatory approaches but works independently of the rational consequences of (a) forbidding or adding any rationally relevant choice options; (b) changing incentives, whether regarded in terms of time, trouble, social sanctions, economics, etc.; or (c) the provision of factual information and rational argumentation. The revised definition also help to make clear that nudges need not be used in the service of libertarian paternalism (think of marketing), but if applied in accordance with the reflected preferences of citizens do offer a central strategy to any libertarian paternalist (which also includes strategies that are not nudges, such as informational campaigns). Finally, this definition allows for a quite simple heuristic – noticed by Thaler and Sunstein themselves (Thaler & Sunstein 2008, p. 8)[2] – for characterizing and identifying aspects of choice architecture that functions as nudges: a nudge is any part of choice architecture that should not effect behavior in principle, but does so in practice (where by principle we mean according to standard economic theory). In fact, this simplifying characteristic of what a nudge is embodies the core insight driving behavioral economics. Nudging At conferences, seminars and in teaching I am often asked the following: “Haven’t we always been nudging?” While it may be tempting to answer “yes” to this question as it leaves the audience (especially policy makers) feeling more comfortable it also leads directly to another question: “So if we have always been nudging, then, what’s new about it?” Thus instead of answering “yes” I usually offer the following answer that relies upon making a conceptual distinction between ‘nudges’ and ‘nudging’, see also (Hansen, Skov & Skov 2016): a nudge is as defined above and we have always been using such attempts at influencing behavior; but nudging is the systematic and evidence-based development and implementation of nudges in creating behavior change. Thus, in this sense it is something new, and today it is this effort that is properly referred to as the field of ‘nudging’ and, as a discipline it is increasing in its influence on public policy and behavior change strategies across the world. A key institution in this development has been the establishment of the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) – or the UK Nudge Unit as it is often referred to – in 2009 by UK Prime Minister David Cameron. It is led by Dr. David Halpern and Managing Director Owain Service and rolled out of government to become partly privatized in 2014. However, BIT is part of a broader trend, which since 2009 has seen nudge units, initiatives, and networks emerging in the United States, Denmark, Singapore, France and Canada, to mention just a few of the many exciting places this is happening. Likewise the OECD, The World Bank and the European Union, have published reports, held meetings, and actively supported research to further examine the potential of nudging, see (OECD 2014), (World Bank 2015) and (EU 2016). Taken together all of these efforts have led to the emergence of the field, yet nudging is only in its infancy.[3] Still, it should be noticed that a common scientific framework of reference unites these efforts. In particular, nudging relies heavily on theories and methodology from behavioral economics as well as from cognitive and social psychology, using microeconomic decision theory as a baseline. In particular, a central focus within the field is the biases and heuristics program of Nobel prize winner Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, which is rooted in dual-process theories of cognition and information processing (Kahneman & Tversky 1979) and made accessible to the wider public by Kahneman’s dual-system theory presented in his famous book Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011). Dual-process theories vary greatly but generally share the overarching structure of positing two types of human information processing — automatic and nonautomatic — in explaining and predicting human behavior (Evans 2008). Using David Marr’s (1982) distinction between computational, algorithmic, and implementation-level theories of psychology, the explanatory function of dual process theories may be located at the algorithmic level of analysis where mental mechanisms that translate inputs into outputs are identified. Identifying processes according to the simplified distinction of whether they operate in an automatic and nonautomatic fashion – i.e., (a) when there is conscious awareness, (b) when there is no goal to start the effort, (c) when cognitive resources are reduced, and (d) when there is no goal to alter or stop the process – these theories thus seek to explain how the supposedly irrelevant features of decision-making contexts systematically influence human decision making and behavior, for a great brief introduction see (Gawronski, Sherman & Trope 2014). In addition to the shared psychological underpinnings, the widespread efforts falling under the auspices of nudging are also unified by the ambition to advance and apply quantitative experimental approaches to field research. The choice (not the invention) of this methodological approach may be ascribed to the intellectual origins in the standard laboratory experiments used in behavioral economics. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are also explicitly formulated as the ideal in, for example, the BIT’s 2012 methodology report, Test, Learn and Adapt (BIT 2012). However, it is important to stress that the objective of nudging is just as much about evaluating the efficacy and policy implications of nudge interventions and examining the potential real-world feasibility and applicability of behavioral insights as it is about extending the boundaries of scientific knowledge. Hence, the aspirations of nudging as currently carried out have much in common with what is usually referred to as real-world research, and the research relationship ideally pursued by stakeholders might best be characterized by a quote given by Hall & Hall (1996) (albeit in a different context): “The research relationship is between equals, and is not exploitative: the client organization is not being “used” merely to develop academic theory or careers nor is the academic community being “used” (brains being picked). There is genuine exchange. The research is negotiated.” Ethics and Policy Despite the various versions of this ideal being adopted by core practitioners of nudging, the cross-sectorial nature of current efforts has undoubtedly prompted some speculation and suspicion. One set of worries pertains to the threat of science being utilized by potentially biased policy makers to manipulate citizens. Another set of worries pertains to whether nudging is being used as an excuse to roll back traditional regulatory efforts. This latter worry has been most prominent in Europeans response to nudging; the US response has been worried more about the former critique pointing to the paternalistic aspects of the approach. Fortunately, most of these concerns turn out to rely on pretty superficial readings of the scientific underpinnings of nudge theory, or on ignoring the challenges that face any attempt at regulating citizens’ behavior, see (Hansen & Jespersen 2013). First, nudges do not only rely on automatic processes, and non-automatic processes are not even necessarily ‘unconscious’ (by analogy: when a plane is on autopilot it does not imply that the pilot is unconscious or unaware of what is going on). Hence nudges and nudging is not characterized by psychological manipulation, as some critics would have it. Still, some nudges do rely on non-transparent measures that transfer responsibilities to citizens in ways that should be regarded as manipulative and thus as illegitimate strategies of public policy in democratic systems (ibid). To this end it does not suffice to say that by principle nudges leave all choice-options from the original status quo available post-intervention since we are dealing with a paradigm that by its nature discards theoretical principle in favor of empirical practice. Instead we need to take the ethics of nudges seriously on a case-by-case basis since nudges comprise such a vast array of different measures that they cannot be evaluated as one. Still, who should provide such evaluation? This leads to my second point with regard to the ethics and policy of nudging. While politicians may indeed be biased themselves the “who nudges the nudgers” critiques fail for at least two central reasons. One: any regulatory effort is directed by potentially biased politicians. Two: while nudges invoke insights about boundaries of rationality, biases, and habits into our choice architecture, nudgingrests on approaches that comprise scientific state of the art methods for trying to detect and avoid such biases. Thus, it seems that nudges should be evaluated just as any other regulatory measure in a democratic system, although it will require expertise to be introduced to guide such evaluation – just as it is the case when it comes to economic and legal measures. Finally, those who fear that applying nudging to public policy and other behavioral change challenges is just an excuse to roll back traditional regulatory efforts miss the central point of this essay. Nudging as well as nudges are fully compatible with and hence should be evaluated relative to standard regulatory measures. However, when it comes to the standards used for evaluating traditional regulatory measures aimed at changing behavior, nudging may actually turn out to raise the bar quite substantially. Thus, nudging should be expected to change the way we do public policy making and delivery due to its introduction of scientific requirements by means of its evidence based standards. The implications, however, should not be characterized as a roll back, but as a shift of paradigm to what may be labeled Behavioural Public Policy. Bibliography Hansen, P.G. & Jespersen, A.M. (2013) ‘Nudge and the manipulation of choice: a framework for the responsible use of the nudge approach to behaviour change in public policy’. European Journal of Risk Regulation (1): 3–28. Thaler, R.H, & Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Hansen, P.G. (2015) ‘Nudge and libertarian paternalism: Does the hand fit the glove?’ European Journal of Risk Regulation Vol. 1, no. 1, 155-174. OECD / Lunn, P. (2014) Regulatory Policy and Behavioural Economics. Paris: OECD. World Bank (2015) World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society, and Behavior. Washington, DC: World Bank. EU (2016) Behavioural Insights Applied to Policy, European Report 2016. Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, Journal of Econometric Society, 47:263–91. Evans, J.S.B. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology 59:255–78 Marr, D. (1982) Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. San Francisco: Freeman. Gawronski, B., Sherman J.W. & Trope, Y. (2014) Two of what?: A Conceptual Analysis of Dual-Process Theories. In Dual-Process Theories of the Social Mind, pp. 3–19. New York: Guilford. Haynes L, Goldacre B, Torgerson D. 2012. Test, Learn, Adapt: Developing Public Policy with Randomised Controlled Trials. London: Cabinet Office – Behavioural Insights Team. Hall D, Hall I. 1996. Practical Social Research: Project Work in the Community. London: MacMillian Notes [1] I.e., the idea that rational decision-making is limited by the contextually available information, the cognitive limitations of the decision maker, and the time available to make the decision. [2] “… a nudge is any factor that significantly alters the behavior of Humans, even though it would be ignored by Econs”, (Thaler and Sunstein 2008, p.8). [3] I am aware that I am only mentioning the top of the iceberg here and thus leaving out loads of interesting initiatives, groups and efforts. For a more comprehensive picture of all that is going on I invite you to visit the homepage of The European Nudging Network (www.tenudge.eu) |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed